Humanity is a species in constant movement, dating from the time that humanity, as we understand it today, didn’t even exist. Homo Erectus left their African homeland to spread far and wide some 1.9 million years ago, and despite the differences between our various genetic ancestors, the need to move and migrate has remained a constant that has endured to the present day.

By and large, the main driver for these migrations has remained the quest for resources to sustain and improve life; nomadic early humans’ life and migration patterns were primarily dictated by the quest for food: the tribe would follow the herds that sustained them, and the rains to reach lands that were fertile and could sustain life.

When humanity began to settle down in towns and cities, learning how to farm and domesticate animals, the nature of the resources being sought changed: now arable land and access to fresh water became the contested resources, and of course the still-nomadic tribes were drawn to these settlements like moths to a flame, posing a danger to the settled communities for millennia.

Even as our needs have evolved, our basic drive to access and control crucial resources has not dimmed. Wars have been fought over salt, spice, oil and rare minerals – something that continues to this very day, and the spectre of wars waged over access to fresh water (a rapidly dwindling resource) is very real.

That’s the problem with natural resources: they are by definition limited and finite. Thus, nations have raced to stake claims to Antarctica and its resources including, but not limited to, potentially harvesting icebergs to provide freshwater supplies. Nor is the world’s surface enough; corporations and governments are increasingly turning their attention towards the ocean floor itself.

Dubbed as a ‘new resource frontier’, the deep seabed can yield a variety of valuable minerals and metals, such as nickel, copper and manganese and also rare minerals that are increasingly crucial for the high-end technologies required to build hybrid cars, wind turbines, and even the mobile phones we are so wedded to. How much of a bounty is there to be had? Japanese geologists estimate that a 2.3 square kilometre patch of seafloor might contain enough rare earth materials to sustain global demand for a year.

But ultimately, scour the oceans all we like, the earth will run out of the resources needed to maintain the lifestyles we have grown accustomed to, and, barring a technological miracle, earth’s rapidly growing and rabidly consumerist population will inevitably strip this planet clean.

When this will happen is up for debate: the WWF predicts that we will be forced to colonise two planets within 50 years if natural resources continue to be exploited at the current rate. Others are less alarmist, but the consensus is that resource exhaustion is simply a matter of when.

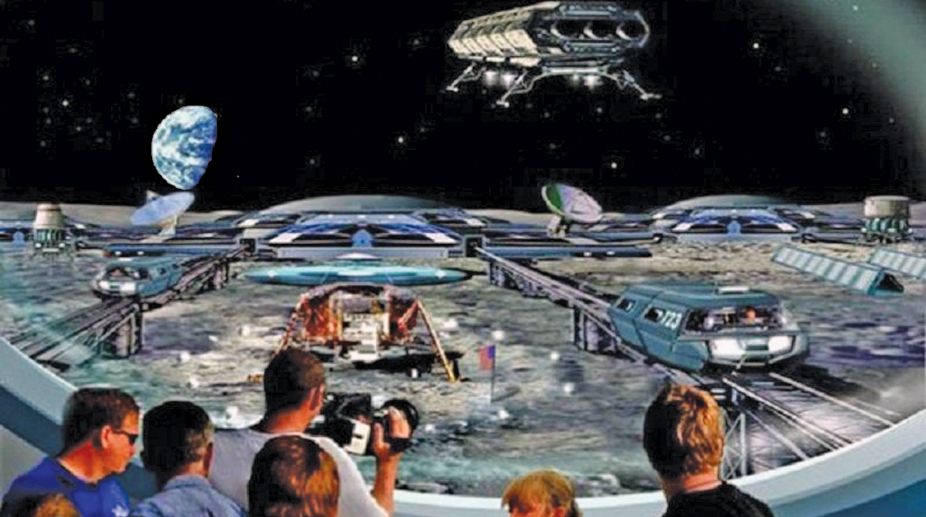

So the farsighted are looking beyond the confines of this blue planet; some plan to colonise the moon and even Mars but others have a more practical and profitable goal in mind: mining the many asteroids speckled around our solar system.

What would that yield? Consider that a single 500-metre diameter asteroid can contain more platinum than has even been mined in the history of the earth and you can get an idea why so many are salivating at the prospect of tapping these resources.

Then consider that there are over 2m asteroids in the asteroid belt, which has been valued by Nasa at a staggering $700 quintillion … that is $100 billion for every person living on earth right now.

Of course, not all of these asteroids are easily accessible but there are about 16,000 near-earth asteroids that several companies already have their eyes on. One of these asteroids is Eros, which is said to yield a value estimated at $15.84 trillion, and to contain more gold than has ever been mined in the history of the earth.

The companies pioneering asteroid mining are planetary resources and deep space industries, and PE has already started the first phase of this ambitious project launching the Arkyd3 Reflight satellite in early 2015 with the aim of identifying the likeliest asteroids for mining purposes. Their next satellite, the Arkyd-6 is twice as big, and was launched into orbit on 11 January 2018.

The end goal is still far away, as efficient resource extraction will eventually require the creation of deep-space mining colonies which will have to be relatively self-sufficient — using the resources found on asteroids to build new bases and even satellites and spaceships — and thus providing launching pads for the human colonisation of the solar system. In time, we may even see a subspecies of humanity emerge, one better suited to life in the low gravity of space stations. One thing is clear though: our salvation lies in the stars.

Dawn/ANN.